When CEO and founder of Basta, Sheila Sarem, was at her graduation ceremony, she turned to the person next to her and asked him what he was doing after college. He shared that he was going into “consulting,” a term Sarem had never heard uttered before. What in the world was consulting? And was that a real job? That baffling moment later inspired her to create a nonprofit start-up that accelerates first-generation learners’ paths to great first jobs (full disclosure: I advise Basta as a board member).

Last year, Basta came out with a fascinating first cut of data about the users of its platform called SEEKR. The data revealed just how critical exposure is throughout the college learning experience and the job search process.

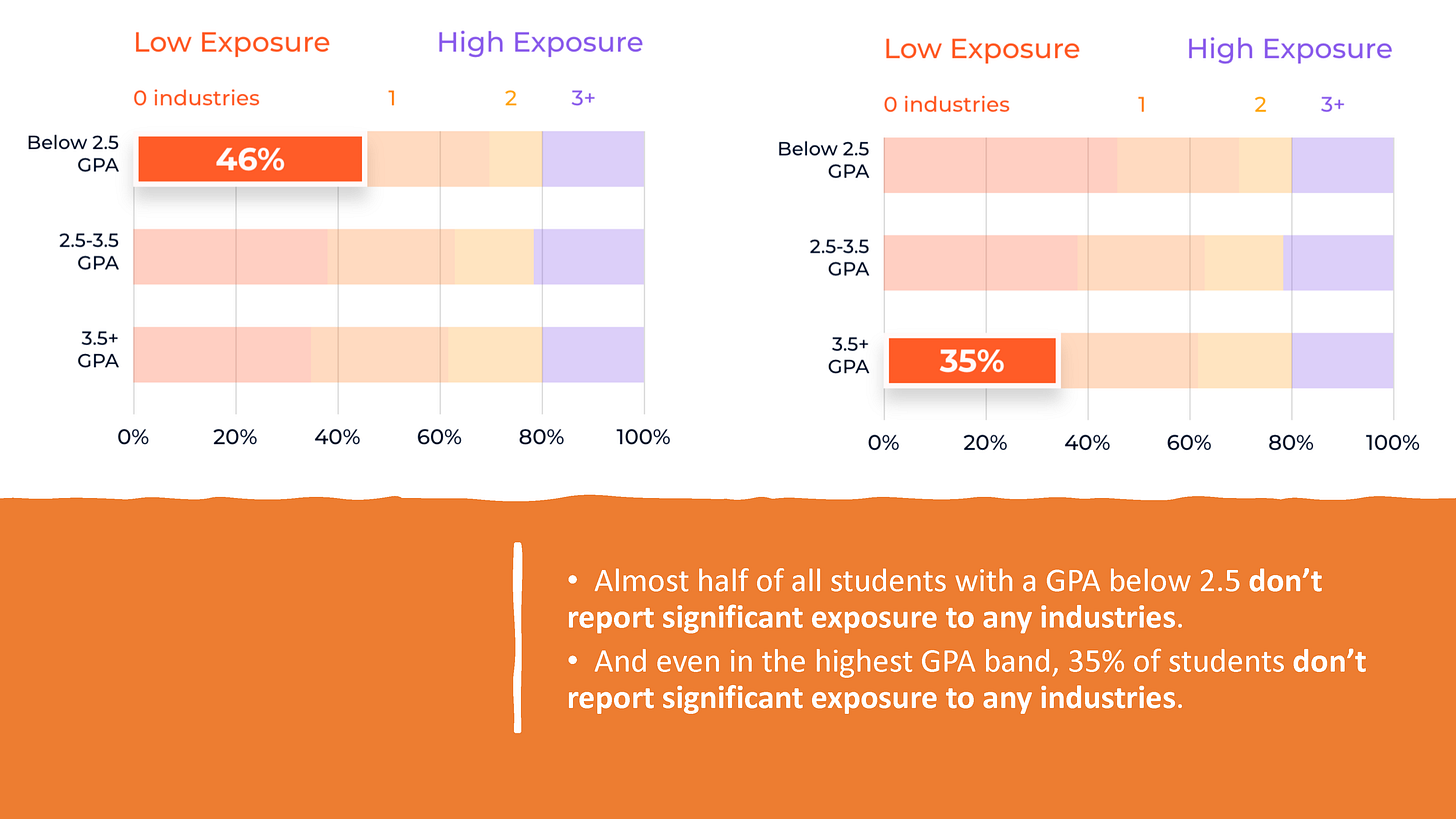

As you might expect, the more students are exposed to and understand different jobs and industries, the more likely they are to find a great first job. What was especially striking about the data, however, was that the learners who reported a high level of exposure to three or more industries were 90% more likely to secure first-round interviews and 100% more likely to advance to the next round of the interview process.

That’s an incredible advantage… that is, if you can get that exposure. What the data also revealed is that most students across all GPA bands—those with very low GPAs as well as those in the highest GPA bands—simply do not get sufficient exposure to a wide array of jobs and industries.

It’s hard to strive for the jobs of the future when you don’t know what those jobs are. In the 1950s, the race to the moon inspired even our littlest learners to dream about becoming an astronaut. They could aspire to these emerging roles in space and aeronautics because they were getting exposed to them in school.

Today, in the absence of exposure, we ask the people around us—our informal social networks—for advice. Unfortunately, our networks can be just as limited in their understanding of jobs as we are; we only know what we know. So, if we don’t know much about the jobs in demand, the people we advise will be similarly limited in their outlook.

What if there was a way in which we could try on different careers and pathways? What if there was such a thing as a career pathway fitting room so that we could better understand the direction we might want to pursue before we make an investment or take out a loan?

One venture-backed company called Springpod has made this challenge its central focus: Helping more people not choose the wrong career or pathway. In its current formation in the UK (Springpod is now branching out to the state of Rhode Island), over 400,000 British middle and high school learners can try a “course taster,” or 10 to 15 hours of a university course from an array of universities (1/3 of the postsecondary institutions in the UK offer a course spotlight on Springpod). Alternatively, a learner can try a one- to two-hour work-based learning experience with one of the 200 employers featured on the platform.

Each of these virtual, video-based learning experiences is filmed and assembled by the Springpod team. For universities, these course tasters connect schools to potential new learners. For companies, Springpod serves as an extended talent pipeline they might wish to tap into. But it’s the opportunity for learners at the heart of this that makes this venture exciting: All British middle and high schoolers now have a way to try on a career pathway.

The world needs more solutions like this so that more young people can try before they buy. Because without good guidance, these decisions can quickly become costly mistakes.

I recently interviewed a few participants from Digilink and codeX, both incredible learning providers based in South Africa that are preparing unemployed youth for digital jobs of the future. Before these participants had discovered these digital skills pathways, they had been stuck:

One woman had spent two years pursuing pharmacy and then switched to two years of journalism. She failed to graduate.

Another interviewee had graduated from university without a job and spent an extra year on a web development certificate that also turned out to be a credential to nowhere.

One young man specialized in operations management at the University of Johannesburg because he had assumed this would help him get into the operations side of business, but he learned much later that the degree alone wouldn’t get him into those roles. He needed work experience, but there were no entry-level positions for which he could apply.

Having used up their funding and resources, each of these interviewees was left to navigate troubled times as one of the 7.7 million unemployed youth in South Africa. They each experienced their own forms of anxiety, depression, and shame as they struggled to figure out their next move.

Exposure is critical in crossing out what we don’t want to do. It’s also the key to aligning our inner motivations with a potential pathway ahead.

The SEEKR data from Basta importantly illuminated the disconnect between learners’ internal drivers and the pathways they were choosing with their limited knowledge of and exposure to various industries. Some college-goers were saying they were highly motivated by status but were going into Human Resources. Others had identified relationship-building as critical to their fulfillment but were choosing finance as their pathway. This isn’t to say that it’s impossible to attain status or fulfillment in these fields, but we are failing to widen the aperture for young people to see that there is more to life than the few professions with which they are familiar.

With greater exposure, a person who is highly motivated by a high starting salary, as an example, might be able to see that beyond healthcare, there is a range of lucrative opportunities in data science, legal, and IT that might better connect to his or her internal drivers.

Some pundits might react to this data and quickly point to internships, externships, co-ops, and apprenticeships as the solution here, but these options are not widespread enough and readily available to all learners. It’s not clear where to look, and not everyone has the social capital or the professional networks required to get a foot in the door for one of these opportunities.

At the same time, it remains unclear whether the work-based learning opportunities of today are connected to the jobs of the future. In the U.S., as an example, only 600,000 Americans enrolled in 27,000 registered apprenticeships in 2022, and only a few of those apprenticeships are focused on the emerging digital skills of the future. I can count on my hand the Department of Labor-registered apprenticeships in coding or data science. Where are the pathways that marry UI/UX design with data analytics, cloud computing, machine learning, ethics, and the philosophy of law. How do we try on that pathway?

This is part of the work ahead for us: How might we design more fitting rooms for the jobs of the future?

Career navigation supports are critical as all working learners seek to make progress in their lives. We need more ways to get exposed to the current and future job market, including all of the career pathways open to us based on our interests, skills, past training, and experiences.

We need more solutions that take the guesswork out of career exploration.

Great article. Sounds like what Parker Dewey is doing with Micro-Internships!