We are not awesome at imagining the future. Part of this is because of what psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky call anchoring, our tendency to rely on the first piece of information we encounter to anchor our thinking. One of my favorite examples is one that Kahneman shares with Peter Diamandis in Abundance:

When people believe the world’s falling apart, it’s often an anchoring problem. At the end of the nineteenth century, London was becoming uninhabitable because of the accumulation of horse manure. People were absolutely panicked. Because of anchoring, they couldn’t imagine any other possible solutions. No one had any idea the car was coming and soon they’d be worrying about dirty skies, not dirty streets….

Thinking about the future can be shitty–literally.

We anchor to what we know. And as Hans Roling puts it, we get “the world devastatingly wrong” and “systematically wrong.” In Rosling’s seminal work Factfulness, he illuminates how “every group of people…thinks the world is more frightening, more violent, and more hopeless—in short, more dramatic—than it really is.”

He illustrates this “overdramatic worldview” by posing this same question to different audiences:

How many of the world’s 1-year-old children today have been vaccinated against some disease?

A: 20 percent

B: 50 percent

C: 80 percent

In other words, is the world getting better or getting worse? Only 13 percent of people get the question correct: C. Oddly, chimps get this question right more often than we do, and they’re just answering randomly. We as humans think hard about this and then inevitably choose A or B, the more pessimistic view.

So, how is it that we can orient more positively in our worldview? How might we keep ourselves from getting down?

Away from the Future of Work

It would help if we moved away from thinking about the WHAT to thinking about the WHO. For years now, researchers have been obsessed with the future of work and quantifying the mass unemployment to come due to the changing nature of work. This quickly devolves into a real anxiety about numbers and the millions upon millions of people who will be dislocated by the future of work: Will it be 47% or 25% of the US workforce at risk of computerization? Would that mean 36 million jobs at risk? Or more, or less?

Massive job obsolescence is just too big, bleak, and amorphous for us to grapple with. Statistics can paralyze us and make a problem like automation invisible to us. It’s like when people talk about global warming and the coming destruction of the earth; these problems are too vast to reckon with.

We have to go smaller and think about people instead. We have to shift from the future of work to the future of workers.

To the Future of Workers

In the research that led to my book, Long Life Learning: Preparing for Jobs that Don’t Exist Yet, my team and I spoke with folks like Monica, Delia, and Caroline who were struggling to make progress in their work lives:

Monica started working at Walgreens right out of high school. She enjoyed the work and saw opportunities for promotion, but with constant churn in the staff and managers, this just never came to pass. Her father had urged her to get a nursing degree, but she chose a medical assisting certificate instead because it was faster and cheaper. Unfortunately, she wasn’t thrilled with the work or the field but didn’t feel like she had a lot of other options.

Delia had to drop out of school at a very young age to take care of her dying father. She ended up getting her GED, marrying, and having nine children. She later divorced her alcoholic husband and has been raising her family alone while working and going to school. She had tried for nursing degrees in the past but was never able to complete the programs because the schedules were not flexible enough, and she lacked transportation. Many of her credits didn’t transfer from program to program, and she had to start from the beginning twice before finally quitting.

Caroline grew up in foster care and never received much guidance about her career. She married young and had a child who was in a severe accident; her daughter now requires ongoing, lifetime care. Caroline works full time, nurses her daughter, and runs accounting and customer service for her husband’s car dealership business. She would love to pursue a degree program so that she can do accounting for her current employer, but she’s been unable to find a flexible enough option that is also affordable.

These stories resonate with each and every one of us because they sound similar to the stories of our own friends and family members who are struggling to make their way in the job market.

Author Simon Sinek talks about the potency of small stories—how impactful Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s image was in his “I have a dream” speech of a little black child holding hands with a white child. This simple image stirs the limbic system of our brain, and we can imagine that more positive future. Sinek elaborates: “And so what we do is we use these individual stories, whether they're true or whether they're hypothetical, as metaphors for the big idea … because we can relate ourselves to the small story.”

Smaller stories move us toward action

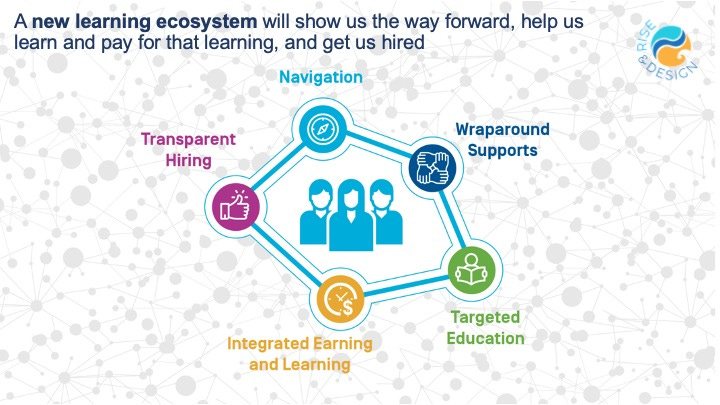

When we switch from the future of work to the future of workers, we can see these three women. Moreover, it’s easier to imagine the solutions that are needed to solve for the specific and recurring pain points in their lives. We begin to see the opportunities to design a better functioning learning ecosystem that is fundamentally more navigable, supportive, targeted, integrated, and fair.

Small stories help us get tactical and focus on removing barriers. We see how we might advise Monica on surfacing the skills she already brings to the table and how they might transfer into an adjacent industry area that she hadn’t ever considered. We think about how to connect Monica with the right competency-based program that gives her credit for what she already knows, so that she can move into an accelerated and flexible online nursing pathway. We think about the kinds of skills that Caroline might need to acquire in financial services that she can pursue online through open educational resources or a local on-ramp program. This way, she can continue to earn a living while developing new skills for a fraction of the cost of a degree program. For all three women, we can advise them on how they might highlight their skills differently in their resumes and hiring interviews to stand out from the crowd.

The Future of Workers, the Future of Us

Small stories remind us that the future of workers isn’t just about Monica, Delia, and Caroline, or those people over there. The future of workers is the future of us. We are the ones who will run into the same challenges and barriers as those who are struggling today as we try to skill up and remain competitive in a rapidly evolving job market.

And therefore, we understand how all of these elements—better career navigation and personalized coaching, access to more targeted educational pathways (the rights skills, the right path at the right time), and ways to build those new skills while earning a paycheck—all need to come together so that we can each demonstrate to a future employer that we are the ones they should hire.

Just like Monica, Delia, or Caroline, we will all need better ways to seek out the relevant information, funding, time, advice, support, and skills training to navigate the job transitions to come.