Jason Hyon is the Chief Technologist of the Earth Science Directorate at NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory. He also happens to be my cousin, so I get to pick his big brain at family gatherings and then quote him in my work.

In Long Life Learning: Preparing for Jobs that Don’t Even Exist Yet, he discusses the need for more learners to learn how to work together toward a larger vision:

We need more engineers in school to learn how to collaborate and work together on ideas in order to develop something bigger. These days, almost everything one person can achieve has either been achieved or is being done. In order to take on the next challenges of science and technology, we need to think together as one and share ideas seamlessly.

That collaboration happens, in his opinion, through more hands-on, problem-based learning experiences.

I recently interviewed Jason for a CGN show focused on STEM careers for young people. This idea of sharing ideas seamlessly is a topic he underscored quite a bit during our webinar. As much as students and parents wanted to know which level of math and other technical skills were required for various STEM pathways, Jason kept returning to the critical core competencies of communication and empathy as the most crucial ones to keep in mind for the future.

Take a look at this short clip:

It’s fascinating listening to Jason talk about how even NASA earth science researchers are prone to measuring and capturing singular phenomena as opposed to thinking holistically about these huge systems problems. It’s ironic that the scientists lost sight of the literal system they were working on—the earth!—and ultimately needed to pull people together and coordinate around the earth’s life cycle.

Although these scientists are working on complex and huge systems problems like climate change, we can still generalize from Jason’s example to see clearly the work for educators in cultivating the next generation of nimble problem solvers.

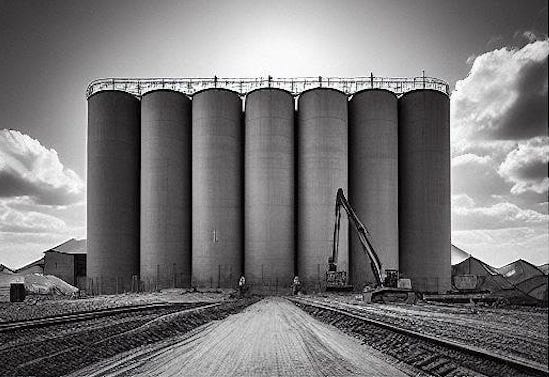

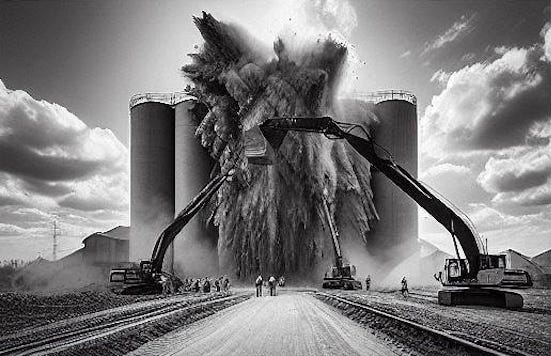

The complexity of the world’s challenges will never be solved by an individual working hard within a single discipline. Heads-down, silo-based work will not lead to new or original discoveries.

And yet that’s precisely how we’re trained: Our education system cultivates us to become high-achieving individual contributors who know how to solve problems within discrete disciplines. We learn how to solve chemistry problems and math problems and physics problems—each within their separate domains—but we don’t learn the deeper connections across disciplines.

At the same time, we’re trained to think that working with others on a high-stakes assessment is a form of cheating. Group projects are somewhat rare and even dreaded by students because their individual grade is tethered to a collective effort.

And now, with the emergence of generative AI and Large Language Models (LLMs), we see certain schools banning ChatGPT and adding plagiarism clauses that forbid the use of AI for classwork. Educators' minds quickly turn to how to prevent students from cheating on tests because our systems are built upon the mental model of an individual having to demonstrate their grasp of new knowledge and concepts.

But we know that whenever humans solve any problem in the world, the solution is and will be, by nature, transdisciplinary. We also know that organizations depend on the communication between and collaboration of many people working across silos.

So, we should be asking: How might we re-engineer learning experiences so that our learners value individual achievement less and orient more as teams of systems engineers?

“We are good at solving one problem at a time,” explains Michael Lawrence of the Cascade Institute. “That kind of siloed problem-solving is not suited to our present predicament…. We need to think more about how the disruptions wrought by global polycrisis can be turned into moments of opportunity to reconfigure our societies.” A polycrisis is a term for multiple crises coming together, such as disease outbreaks alongside global warming.

We now live in a world that doesn’t afford us the luxury of solving one problem at a time. We are beset with wicked and thorny problems occurring in parallel. Our thinking will inevitably be far too narrow when we stick to our disciplinary boundaries.

In order to solve any seemingly intractable problem of the future, learners will need to engage in de-silo-ization.

We must develop intellectual dexterity—flitting across domains—while engaging deeply in these human skills of empathy, communication, teamwork, and collaboration. Technical skills have their value, but even in the most technical or scientific of circumstances, we cannot move forward without these most basic human skills to break down barriers and galvanize our efforts to solve the world’s most pressing problems.

Dr. Michelle R. Weise is the author of Long Life Learning: Preparing for Jobs that Don’t Even Exist Yet and leads Rise and Design, a strategic consulting and advisory service for businesses and higher education institutions.

Completely agree. The only way to tackle complex problems, which are typically interconnected with other problems, is an interdisciplinary approach with broad perspectives.